Others with Vitiligo

▢ A few observations on the below articles:

- Look at how the articles frame vitiligo: 1978: Incurable disease, 7/2009: skin disorder, 8/2009: vitiligo

- In 1978 vitiligo was treated like the ‘unnamed’ terrible disease – later it was still unnamed but less threatening – then named – now people are outspoken on social media; models with vitiligo

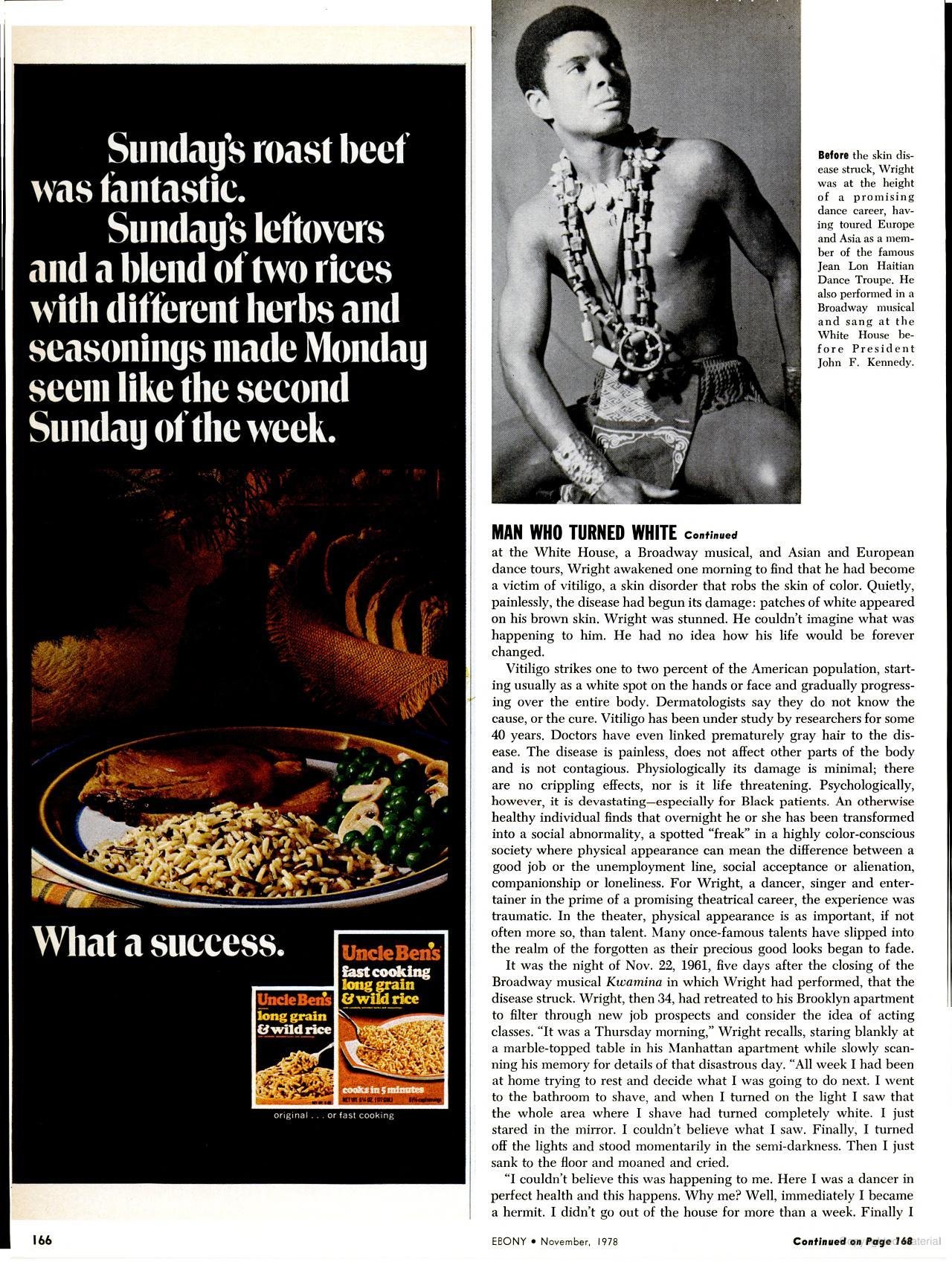

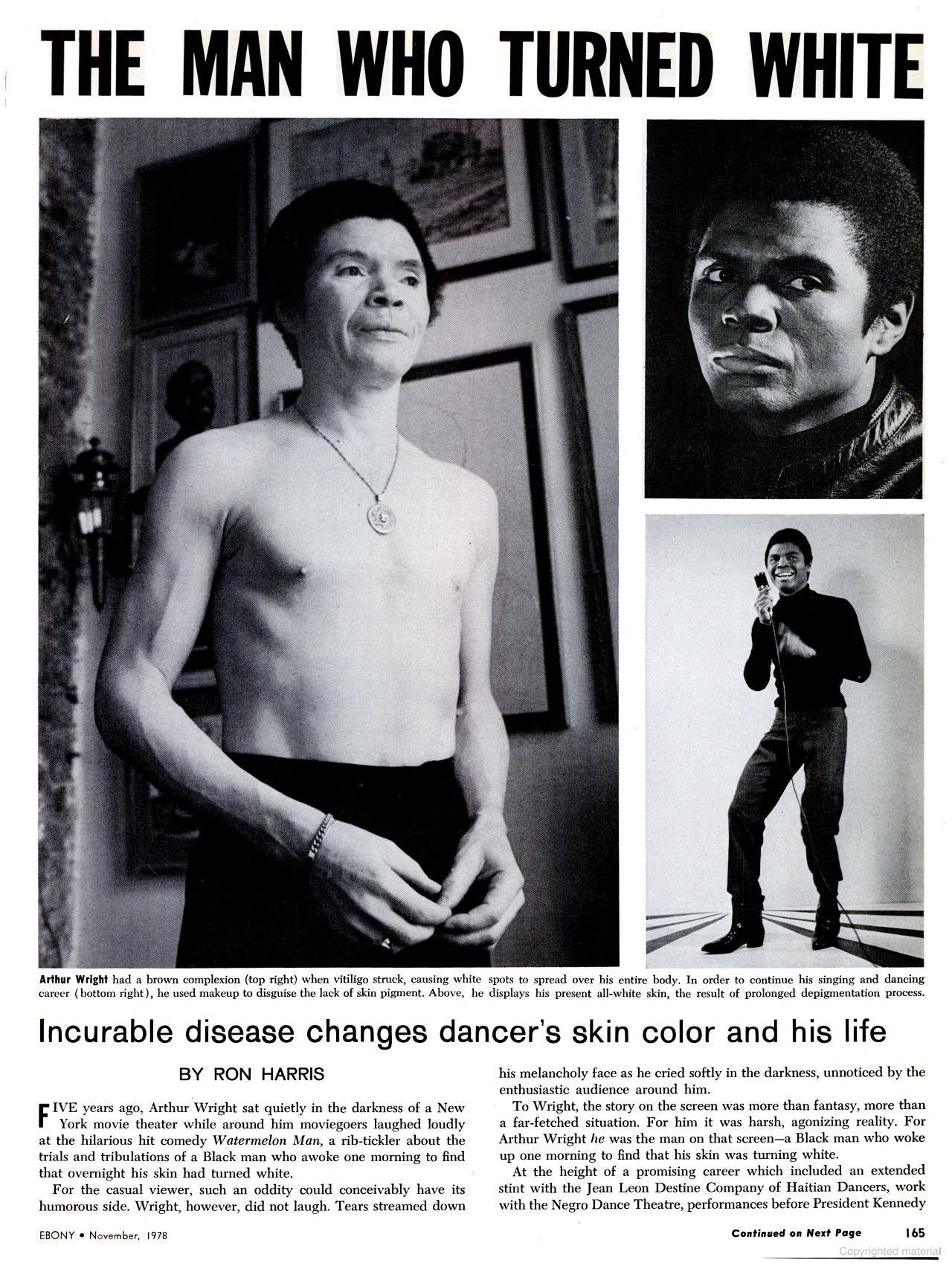

Arthur Wright

Ron Harris: “The Man Who Turned White -Incurable disease changes dancer’s skin color and

his life”

Arthur Wright – vitiligo

▢ I believe he could be perceived as Asian now. If I were unaware of his vitiligo, I might have assumed he had undergone cosmetic procedures.

Context: On the cover of this issue is Diana Ross, on the occasion of ‘The Wiz’ being released. It is likely that Michael knew about Arthur Wright’s story.

Transcript

by JS; [edits my own]

In the bathroom of my apartment the makeup looked even, the same color as my face. But in the sunlight it was a different color than my skin. I looked like a clown. I ran back to my apartment and cried.”

What followed that memorable day was eight years of suffering, Wright says –eight years of being laughed at, talked about and singled out in crowds. They were years of applying facial makeup daily. Eventually, when the disease spread to the chest, thighs, arms and legs, makeup had to be applied to Wright’s entire body before he appeared on stage. Meanwhile he consulted eight dermatologists in New York, Chicago and Washington, and even in Europe. Each offered a different cure. None worked.

There were numerous pills, lotions, creams and balms which purportedly would restore Wright’s skin to its once rich brown color. None worked. There was deep depression and a short barbiturate addiction, the results of a cure prescribed by one dermatologist. There was the loss of friends, the loss of lovers, and there was fear – fear that the makeup mask he so diligently applied each morning would be discovered, his condition revealed, and the rejection that usually followed the unmasking repeated.

[…]

‘Depigmentation seemed to me to be the only way out.‘

Under Dr. Stolar’s care he underwent depigmentation, a process of removing color from the skin by applying a special cream. Dr. Stolar has prescribed the treatment for more than 50 Blacks afflicted with the disease.

“It took three years to make the decision to have that done,” Wright says. “I just couldn’t believe that there was not some way I could get my own color back. Plus, I didn’t want people thinking that I wanted to be White. During that time everything was ‘Black Is Beautiful’ and ‘Be proud of being Black,’ and here I was getting ready to undergo a process that would turn me white.

But I decided that I couldn’t live as I was for the rest of my life. I couldn’t continue my life running away from people, living partly as a hermit. I had to do something, and depigmentation seemed to me to be the only way out.”

‘it was like standing in front of a mirror behind someone else, making that person up. […] without the makeup, it wasn’t me.‘

It took five years for the process to be completed, but Wright stopped wearing makeup after only three months when his face became all white. “I was so happy not to wear another speck of makeup that I didn’t know what to do,” he says, clasping his hands in a moment of jubilation.

“You have no idea what a relief that was. I was so glad to be released from that bondage. It had become such a routine that it was as natural as breathing, as brushing my teeth or combing my hair.

Every day when I went to the bathroom for the ritual, it was like standing in front of a mirror behind someone else, making that person up and then superimposing myself. You see, without the makeup, it wasn’t me. I had to recognize my own face before I could go out, and that person with all those spots was not me.”

[…]

Wright says he is no longer the focus of stares and snide remarks, though he admits, “I get the strangest looks from Orientals. […]

‘I became that sort of hermit. […] The whole thing caused me to lose faith in people and distrust them.‘

I was a very outgoing person when this happened, always on the go, doing things and loving people. But after this I became that sort of hermit. I lost a lot of friends, and that hurt. I was afraid of people, afraid of being rejected. I had no sex life, for years and very little when I started back. I ran away from anybody who showed any interest in me. I didn’t want to be rejected, and I couldn’t know if they would accept me with those spots all over my body.

“I met people and they didn’t want to shake my hand because of the spots. I was a freak. When I rode the subway people would laugh, giggle and point at me, because when my makeup came off my lips they were pink and there I was with this dark complexion and pink lips. I found that a lot of people that I thought were my friends were just phony people, and I started getting rid of all phony people around me. A lot of people let me down because they fitted in the category that I didn’t think they fitted in. The whole thing caused me to lose faith in people and distrust them.

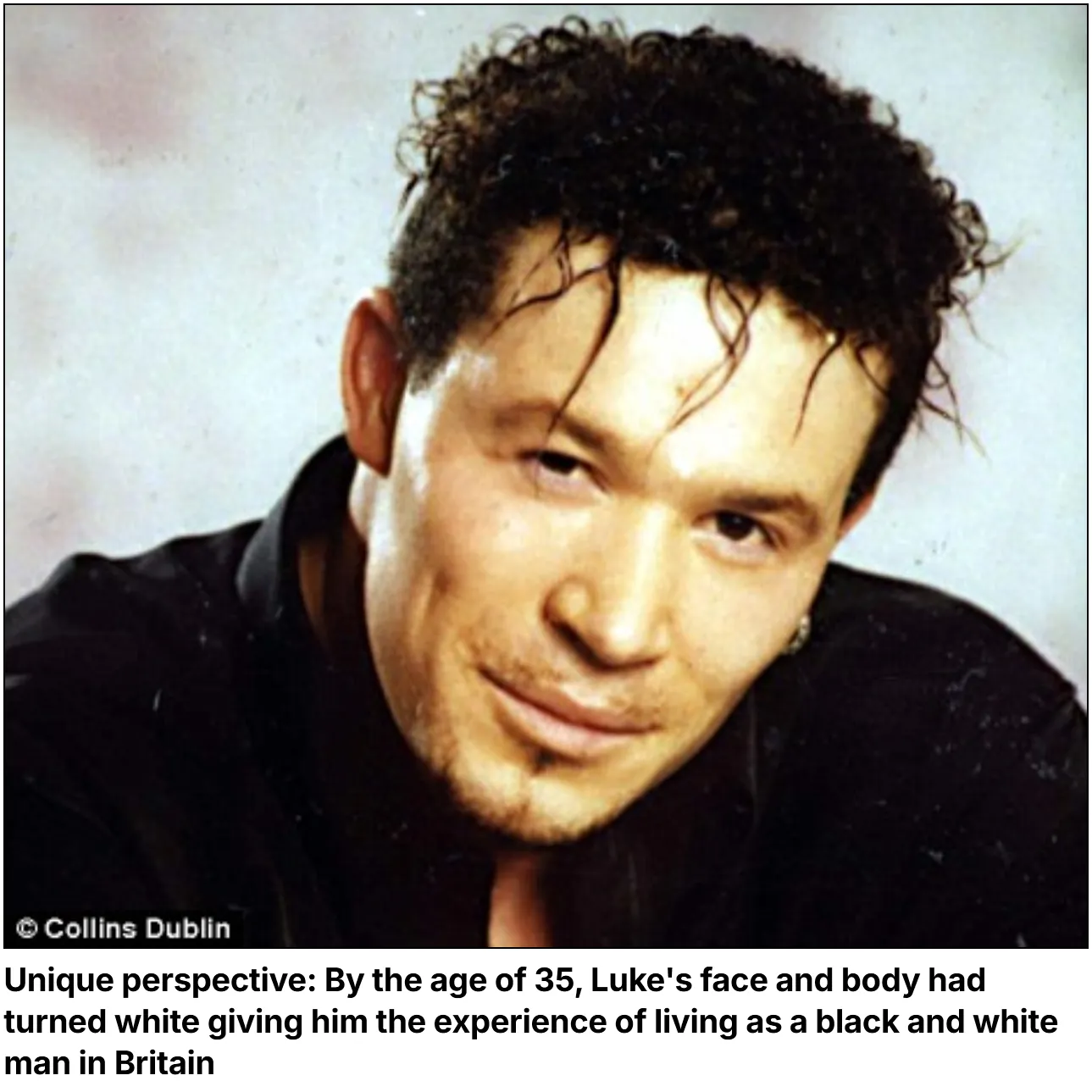

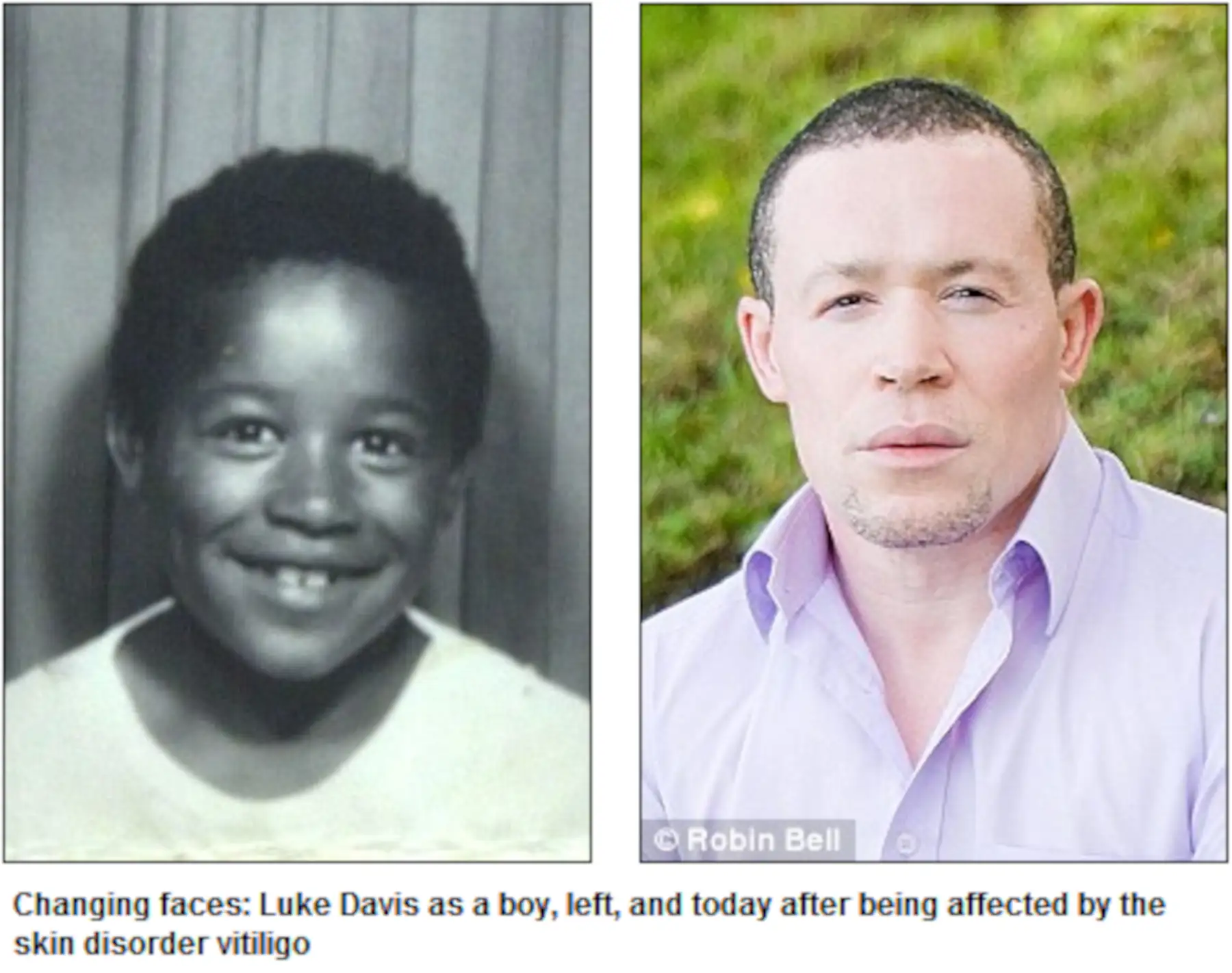

Luke Davis

Luke Davis:

“I turned from black

to white:”

Luke Davis from kid to adult – vitiligo

Transcript

by JS; [edits my own]

Today, at the age of 44, as a result of the skin condition vitiligo, I am white. Were you to see me in the street, it wouldn’t cross your mind that I’m anything other than a typical middle-aged Caucasian man. The only reminder of the colour I once was is a circular patch of dark skin just 1cm wide at the top of my back.

[…]

‘I want people to know that, despite my fair skin, I am a black man.‘

Yet, despite all this, I can’t say I am truly content. Once, all that mattered to me was fitting in and being accepted, and I would have denied my heritage to achieve it. But I’ve come to realise that to deny my heritage is to deny who I am. Often, when I look in the mirror, I am shocked by the unfamiliar white face staring back at me, and I can’t help but mourn the colour that I once was. I want people to know that, despite my fair skin, I am a black man.

[…]

Like any child, I just wanted to fit in. I had no idea what was happening, but my skin continued to fade from black to completely white in patches. When I was six, I noticed lighter patches appearing on my fingers. Within a month, the tips of my fingers were white. The other children – and even the nuns – would grab my hands in fascination, while I tried to wear gloves as much as possible or else keep my hands firmly in my pockets. At seven, my toes and groin had turned a blotchy white, and by eight the transformation was slowly pushing down my thighs. I’d been ridiculed and abused because I was black, and now I was even more of an oddity.

[…]

All I wanted was to be completely white. […] (My mother) was horrified when she saw the state of my skin, and assumed the nuns were bleaching it. When I told her they weren’t, she insisted on taking me to see a skin specialist in London. It was there, after a number of tests, that I was diagnosed with vitiligo – a chronic skin disorder that affects around one per cent of the population and causes depigmentation. The doctor’s prognosis was that the vitiligo wouldn’t spread much farther, as in its most common form it does not cover the entire skin. I was also told there was no treatment for it. […] I’d been sure the doctor would have a remedy to turn me either wholly black or white, so that I’d no longer be perceived as a freak.

Today, many theories exist to explain vitiligo. The most popular is that the body’s own immune system attacks pigment cells.

‘It’s a terrifying feeling your identity is about to be changed and you have no control over what is going to happen’

It has been established, too, that genes predispose some people to vitiligo, and environmental factors such as psychological stress and hormonal changes can play a part. But whatever the causes, the white areas on my skin continued to spread.

[…]

It’s a terrifying feeling to think your identity is about to be changed and you have no control over what is going to happen. […]

I am now getting used to my white face and finally learning to accept myself. One of the best things I’ve found about being white is the anonymity that comes with it. I am not seen as an obstacle, or a potential problem, and it’s much easier to mingle within a group.

[…]

I will always remain fiercely protective of my black origins and I recently walked out of a wedding after a racist joke was made.

[…]

If I had the choice and could live in a world without racism, I would choose to be black. But whether my skin is black or white, I am still the same person inside.

Darcel de Vlugt

Transcripts

by JS; [edits my own]

‘I have a hard job convincing people that I was actually born with dark skin.’

In a case of extreme rarity, the skin condition vitiligo has taken the pigment from her entire body. Experts say they have never come across such a striking change and she says: ‘I have a hard job convincing people that I was actually born with dark skin.’

[…]

Doctors diagnosed vitiligo, the same condition said to have affected Michael Jackson.

By the age of seven, white patches had appeared on her legs along with white spots on the rest of her body. These gradually grew bigger until, when she was 17, the transformation was complete. ‘My father worked for the United Nations and we travelled the world a lot with his job,’ said Darcel, now a fashion designer in London. ‘My family believe the stress of moving at such a young age brought on the condition.

[…]

Miss De Vlugt was given the option of bleaching the remainder of her skin as her body started to change colour, but she decided against it. She said: ‘I believe that Michael Jackson had vitiligo and had patches of it on his body, then he bleached the rest so it had an even look. ‘But I didn’t want to bleach it as it would mean it was irreversible, and I had hoped that all the treatments I had been having would work instead. ‘But now my body is completely white all over, with not a patch of brown left, so I wouldn’t have needed to bleach any remaining skin anyway.’

Doctors told her parents she had an autoimmune disorder called vitiligo. Affecting as many as 3 percent of all people, it is usually not noticed in people with light skin — but is glaringly obvious in people with dark skin.

[…]

Even today, she has a hard time convincing people in her native land that she is really a Trinidadian. When she goes into a black club, people look at her as if wondering what that white woman is doing there. And when she travels in white society, she doesn’t feel the same as all the people around her whose skin is so similar to hers.

[…]

‘It’s so hard to go through something that’s visual, you know?’

“I really, really hope that by doing this, other people can see that it’s just something that makes us look different. It’s not different in any other way. It’s not contagious. It’s not life-threatening,” she said.

And yet, she added, “It’s so hard to go through something that’s visual, you know?”

https://www.today.com/health/rare-skin-illness-turned-her-black-white-1c9403530

‘I would just kind of shy away and do my own thing‘

(A friend) “used to say things about my skin; she told me once that I was ugly. And I just remember it just brought my whole world down. Not because of what she said, but because when she said it everybody else stood there and said nothing. And that really broke my heart, because I think as Martin Luther King says, it’s the silence of your friends that you remember, and that one really, really hurt. So we had a lot of conflicts, but I would just kind of shy away and do my own thing,” she said.

https://www.iamagirl.ngo/posts/when-all-you-seek-is-acceptance/

Winnie Harlow

Both photos are screenshots from her Instagram account. Harlow is very open about her condition, which makes it possible to track how her vitiligo progresses.

This is invaluable for understanding the condition.

“Child with vitiligo”

Photograph: Pexels/Zaid Mohammed

“Serious

black man browsing smart-phone in studio”

Photograph: Pexels/Armin Rimoldi

“Young man extending his hand”

Photograph: Pexels/Ben Iwara

“Man in a cap leaning against a car”

Photograph: Pexels/Felix Mejica

June 25 is World Vitiligo Day

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_Vitiligo_Day